Once upon a time, building an Android app to do work in the background was easy: Just build an Android Service, and you could run whatever code you wanted for as long as you wanted. But things started to change with Android 8 and again with Android 12. Today, Android Services are often more trouble than they are worth.

The Rise of the Foreground Service

With Android versions 8-11, Google limited Android Services to run only about 10 minutes in the background before being force stopped by the operating system. Yet Google left a big loophole with what is known as a Foreground Service. These once rarely used service types were introduced back in 2009 with Android 2.0. They work like a regular service except they also show a persistent notification to indicate to the user that the service is running.

Foreground Services have always been confusing to developers, not least because the name is super misleading. Apps running Foreground Services, do nothing to alter whether your app is treated as being “in the foreground” by Android. An Android app is considered in the foreground if and only if the screen is not locked and a visible activity is on the screen (not just a notification). If either of these conditions is false, the app is treated as if it is in the background by the operating system, and any restrictions for backgrounded apps still apply – regardless of whether there is a Foreground Service active. This is a critical distinction, because over the years, Android has added lots of little restrictions on what apps can do when they are not in the foreground.

But Google’s Android 8 loophole for Foreground Services made them super popular. A Foreground Service, unlike a regular Service, could run for an unlimited amount of time in the background. An app would just have to make this obvious to the user by having that persistent notification visible. This is what Google Maps does to keep running navigation in the background on those multi-hour car trips.

The Fall of the Foreround Service

This worked great for four years, until Google cracked down on Services again last year with Android 12. The new restrictions limit the specific times an app could start a Foreground Service. If the app is in the foreground already, no problem. But if the app is in the background, then starting a foreground service is generally prohibited – unless one of a dozen often obscure special cases apply.

What’s worse, it is often unclear whether a special case applies, and there is no API to ask Android if one applies. You just have to try to start the service and see if Android throws an exception:

try {

val intent = new Intent(context, MyService)

context.startForegroundService(intent)

}

catch (e: ServiceStartNotAllowedException) {

// This happens on Android 12+ if you try to start a service from the background

// without a qualifying event. Why was it not allowed? What the heck do we do now?

}

This can be very frustrating. For example, the Android docs say that any event requiring a BLUETOOTH_SCAN permission should allow a Foreground Service to be started. But whenever I tried the above code right after receiving a Bluetooth scan callback, I always got the exception. After spending hours digging through Android Open Source files, I saw no evidence of any special privileges granted by Bluetooth scans – only by Bluetooth connection events. So I needed alternatives.

The Death of the Android Service?

Android’s official docs suggest using a WorkManager, which is just a fancy backward-compatible wrapper around scheduled jobs. A JobService is a specialized type of Android Service designed for one time or periodic tasks lasting up to a few minutes.

But sometimes you need to perform tasks all the time in near real-time. This is often the case with Bluetooth or other radio signal-based apps that require you perform work at a very specific time when another radio happens to be nearby. You can’t just wait up to 25 minutes for the Android job scheduler to kick in and hope that the external radio will still be around at that time.

Given that Android Services have become such a pain, why do we use them at all?

When I originally posed this question, it was rhetorical. I believed that Android Services are the only way to do work in the background, or that Android Services get special privilege to run that code running outside services do not. But then I checked my premises. And as it turns out, it’s simply not true. The fact of the matter is that Android Services are simply not needed to run code in the background. When they are used, they give you no special background running capabilities. In fact, as we have described above, Android Services unleashes a whole host of new restrictions on running in the background.

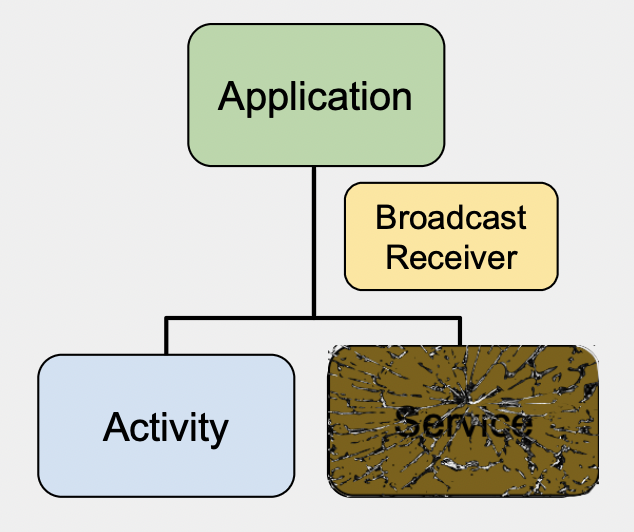

The only reason apps use Android Services for background work is because Android’s original designers intended them to be used that way, and designed a bunch of APIs into the SDK to make it easy to set up componentized background code and have each component be able to communicate with other components. This made great sense back when Android Services were flexible and unhindered by today’s restrictions. Why not use the tools that Android designers laid out for you? As people did this, more and more tutorials were written and questions answered on StackOverflow.com. Today, Android developers generally believe that if you want to run code in the background, you must use some kind of Android Service, even if it is relegated to a JobService managed by the WorkManager.

But as Yoda would say, you must unlearn. You don’t have to use Android Services. The constructs made sense once upon a time, but today they are like an over-regulated municipality. The Android citizenry needs to wake up, and move outside the city limits to regain its freedom.

An Alternative Approach

Here’s an example of what you can do instead: use a combination of BroadcastReceivers and threads. Much like a Service, a BroadcastReceiver can be used to receive all kinds of sensor, radio, or other events (BOOT_COMPLETED is a super important one) and trigger your app to start executing code. You declare one in your AndroidManifest.xml like this:

<receiver android:name="MyBroadcastReceiver" android:exported="false">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.BOOT_COMPLETED"/>

</intent-filter>

</receiver>

And then write code to back it like this:

class MyBroadcastReceiver: BroadcastReceiver() {

override fun onReceive(context: Context?, intent: Intent?) {

if (Intent.ACTION_BOOT_COMPLETED.equals(intent?.action)) {

Log.d(TAG, "The phone just booted.")

// Set up for any other programmatic broadcasts here

val filter = IntentFilter(BluetoothAdapter.ACTION_CONNECTION_STATE_CHANGED)

context?.registerReceiver(this, filter)

}

// This cannot execute for more than 10 seconds otherwise Android kills your app

}

}

In the example above, the BOOT_COMPLETED is often useful, because as of Android 8, lots of other broadcasts in Android are not allowed to be registered in the Manifest — you have to register for them programatically. This gives you an easy way to do that so your app is always listening for them.

The trick with a BroadcastReceiver is that the operating system only gives you 10 seconds to exit the onReceive method (called on the main thread) before it kills your app with an Application Not Responding condition. But don’t worry, just start a new thread. Then you can execute whatever code you want however long you want. Like this:

val executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(1)

executor.execute(Runnable {

while (true) {

Log.d(TAG, "I will log this line every 10 seconds forever")

Thread.sleep(10000)

}

})

The code above doesn’t do much – it just prints out a log line very 10 seconds forever. But you can do whatever you want here – scan for Bluetooth devices, make network calls, etc. And because the code runs on its own thread, not the main thread, it doesn’t violate any Android rules. Voila! We are now running code indefinitely regardless of Android’s service restrictions!

I used these same techniques to make the Android Beacon Library be able to range for Bluetooth Beacons continually without an Android Foreground Service.

You can try this example yourself in this Gitub repo. The app has no UI – just a blank white screen. But run the code and view LogCat and watch its logging keep going. The code in the repo organizes things a bit more by adding a custom Application class, and moving all the initialization to the onCreate method instead of the BroadcastReceiver. Putting code in the Application onCreate method is a great way to ensure code is executed just once each time something starts the app (unless you configure a multi-process app – and please don’t!) If you run this code it will keep logging every 10 seconds forever. If you reboot the phone, it will automatically restart and do the same.

Of course, this roll-your-own approach doesn’t mean that the code actually will run forever. The operating system will still go into deep sleep and shut down the CPU at various times, causing the code to pause for awhile before resuming. (This is also the way code running inside Android Services behave.) And your app can still crash, get terminated due to low memory, or be shut down by proprietary task killers (also just like regular Android Services). But these are normal caveats, and there are solutions for all these issues. The key point is that the sample code doesn’t break any Android rules – it is perfectly legal to not use Android Services for long-running background work.

Some will certainly argue that such a roll-your-own approach is a bad practice, and that you should use standard design frameworks like Android Services whenever possible. While this may be true, it is also true that the increasing restrictions that Google has placed on Android Services mean that “whenever possible” is becoming increasingly rare.